HAMLET!

We’re finally starting him today, and I love, love Hamlet, the poor kid. You’ll see why. On Tuesday you learned a little about Shakespeare and tragedies, as well as completed exercises to immerse you in the English of his day. Today we’ll discuss the play itself and get you started reading and responding.

Hamlet is so huge, it’s like the Grand Canyon. In photos, you see little sections. When you get there, you realize it’s 20 times larger than you ever expected.

But you can’t explore every facet; you can only take a hike or two. That’s what we’ll do: delve into the most interesting parts as we read. But realize that some universities spend an entire semester on it, and could keep going. We can’t. Even if I could, it’d crush you and me.

So we’re going to take an excursion through it, see a part of it, and realize that there’s enormous amounts we can’t even touch. But I hope to give you enough of a taste of it to understand why it’s such an important play, still 400 years later.

Overview of drama and key terms:

Because we have no descriptions in drama, its biggest part is the text itself.

- Dialogue: conversation between two or more characters

- Monologue: single character, how they reveal their thoughts to the audience

- Stage directions, which in Shakespeare are minimal: playwright’s instructions about movement, action, gestures, body language, and sometimes facial and vocal expression

Kinds of characters:

- Protagonist: the central character, leading the play, “main struggler”

- Antagonist: opposes the protagonist, “who protagonist struggles against”

- Round characters—dynamic, developing, growing and changing.

- Flat characters—static, fixed, unchanging, no growth.

- Stereotype or Stock characters—typical minor characters you find everywhere, like the surly barman, the flirty maid, the corrupt politician, the nosy neighbor, etc.

- Ancillary characters—these set off or highlight the protagonist in various ways. The most common is the FOIL—someone who is compared and contrasted to the protagonist.

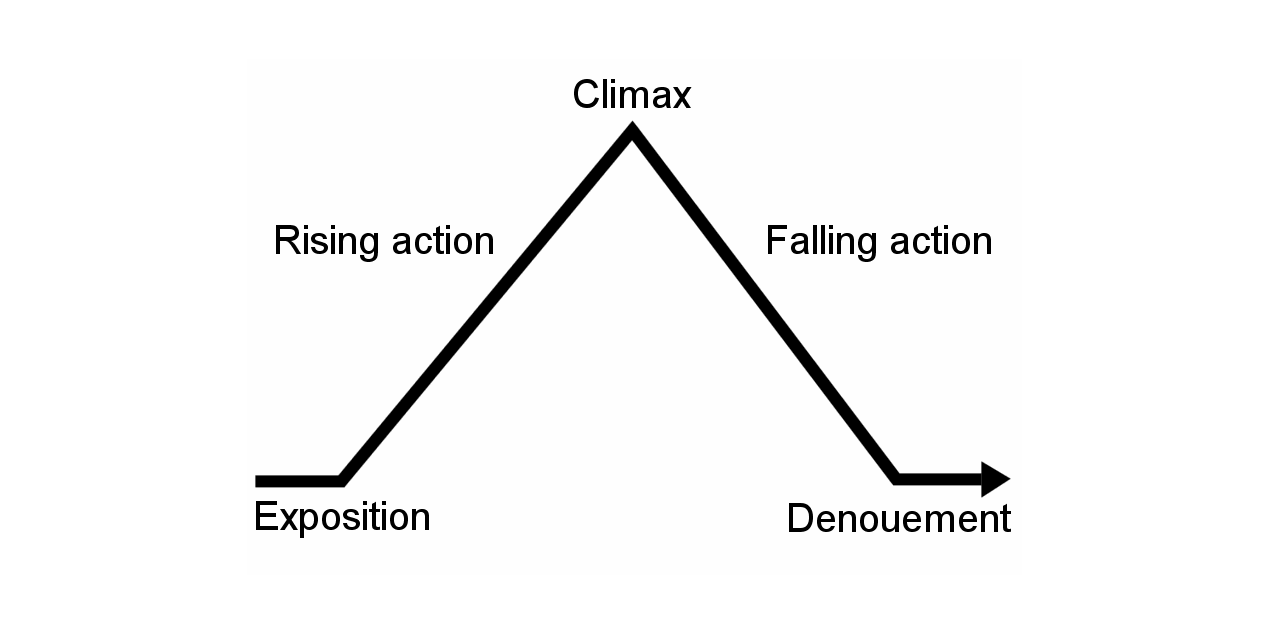

Plays have a common structure. You’ve seen this setup before with short stories.

But with tragic plays, the labels are a little different.

- Exposition or introduction—sets up the play, cues the listeners as to the setting, etc.

- Complication and development (rising action)

- Crisis or climax (main problem reaches its height)

- Falling action (picture an explosion, with shrapnel falling down around you)

- Denouement, resolution, or, in a tragedy, the catastrophe (because nearly everyone will die; oops, spoiler)

HAMLET ATTITUDES as you wrote up on Tuesday with the substitute. What do you believe?

- Power is a corrupting force

- Revenge is the best way to get justice

- You should always trust your family and friends

- Ghosts are real

What do you already know about Hamlet? (Ever see “The Lion King”? Loosely based on Hamlet.)

It’s best to understand the play’s end from the very beginning, so I’m going to commit major spoilers today with these handouts.

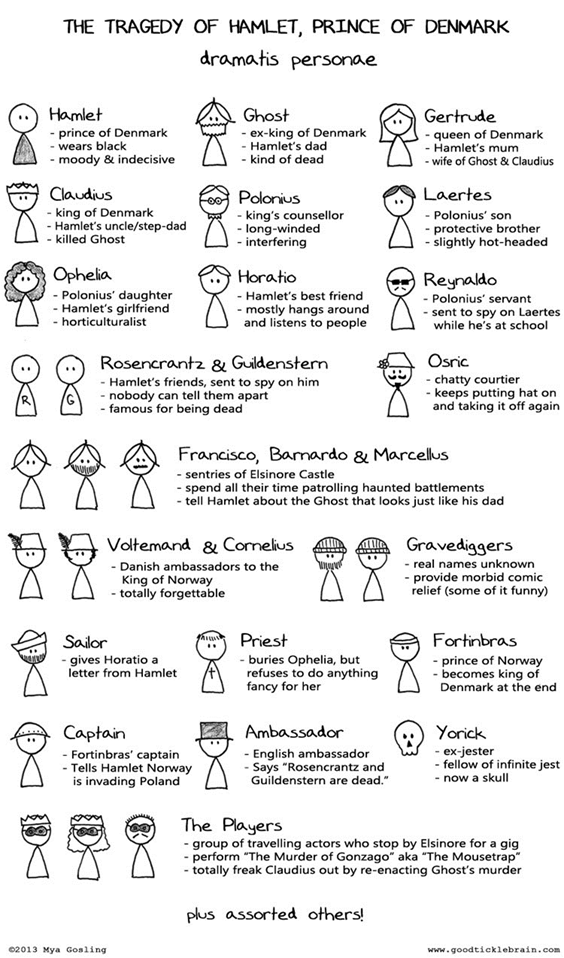

First, the characters:

It’s important to understand the entire story before we start reading, so here come the major spoilers!

Plot Summary of Hamlet (From California Shakespeare Theater)

For each night’s reading you’ll also complete a reading log which, a couple years ago, students dubbed Ham Log, and that works. Follow the directions on that link. You will need to read AND write EVERY NIGHT, so do NOT FALL BEHIND!

HOMEWORK: Read Act 1 Scene 1 (1:1) and Act 1 Scene 2 (1:2). We began Act 1:1 in class but didn’t finish, so finish it on your own.

IF you find the language daunting, even with the footnotes, then you may also go here to read: No Fear Shakespeare. It shows the original text on the left, the updated translation on the right. I confess I go here to puzzle out difficult passages or figure out references and idioms that leave me scratching my head. Please still read the Shakespearean language, then come here for clarification as needed.

AFTER you’ve read both scenes, complete ONE HAM LOG for both scenes, completing 3 of the 7 activities (your choice). Create a Google Doc with your name and Ham Log in the title. Every day you’ll update this log. I will check on it a few times each week and give you credit for each log entry you complete. Do NOT fall behind! You’ll hate life and everyone in it if you do.

Tomorrow in class we’ll go over those two scenes, clarify language, and watch those scenes in the 2009 production of Hamlet. Shakespeare isn’t meant to be solely read, but to be watched and experienced. I believe you have a better handle on the text if you read, write about, then observe the text being performed every day.