HAMLET Act 5:2 The END! (I already miss him.)

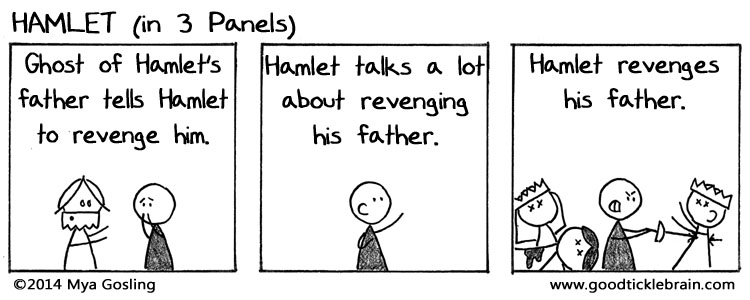

I guess we could have just read this comic and be done with it:

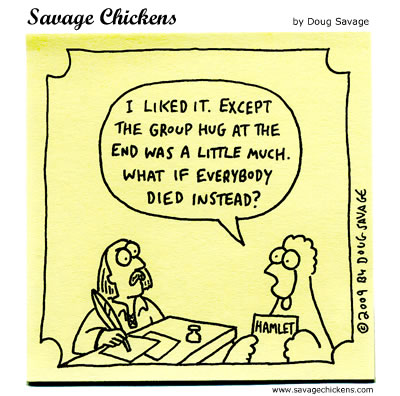

Or we could have read this version:

But I thinks it’s far more rewarding to take the scenic route as we did. Let’s discuss what we watched yesterday, but didn’t get to discuss: the fight at the funeral.

Act 5:1–Why do you think Hamlet rushes out and proclaims his love for the dead Ophelia? Does he really love her? Here’s a theory–he did really love her. So then why reject her and push her away earlier? To protect her, until he’d finished the revenge his father demanded. Maybe he didn’t want her to be caught up in all that he had to do to dispatch Claudius, so he put distance between them, which he intended to fix once Claudius was gone. Maybe he did plan to marry her and make her his queen, but everything has gone awry.

Or, less romantically, he really didn’t love her, but is caught up in the moment of the funeral, the shock of seeing yet another death, that he rashly rushes out to proclaim that he loved her, too. Which approach do you think is most accurate? (Hint: True love wins. Or doesn’t. I’m a romantic at my cynical heart so . . .)

The scene sets easily sets up the duel (and in the 2009 production, you can see Claudius’s sly smile as Laertes and Hamlet are fighting–“Ooh, this is too easy.” I’m surprised he doesn’t start rubbing his hands like a James Bond villain in anticipation).

WATCH the end of the video covering Act 5:2, 2:46:42–3:01:00

Again, many sections in the video are skipped, but the major points (except for two–HAMLET’S ESCAPE! and FORTINBRAS!) are here:

Hamlet’s escape and the undoing of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern: they had a letter to present to the king of England, which Hamlet found one night while wandering around. It was Claudius’s demand that Hamlet be killed. Now that Hamlet realizes that he’s a target, that seems to finally convince him that Claudius must go! He writes another letter, seals it with his father’s ring, and lets R&G deliver that to king which says, essentially, “Kill the bearers of this letter.” Clever, Hamlet, clever.

Hamlet then expresses his regret about getting all up in Laertes face at his sister’s burial. “He was just so upset, so I got all upset . . .” Competitive boys, I wager. But he realizes how much they have in common at that moment, both losing fathers and Ophelia.

Enter Osric, guy who has a position in the castle only because he owns lots of land. Money, not matter, is what gives someone position. He’s sent to tell Hamlet (through far too many big words that he runs out of them) that Claudius has set a bet that he could beat Laertes in a fencing duel. Now, to me this seems like really weird timing: we just had a burial, it was awkward and emotional, and so . . . Hey, I know! Instead of mourning, let’s have a fun duel with bets and drinking (that Claudius is always looking for a reason to drink–Hmm, we just may have found one of his major failings). Hamlet’s like, Sure, whatev. This place is making me feel weird. He feels the odd vibe (calls it something that “would perhaps trouble a woman”–suggestion a “woman’s intuition” feeling), as does Horatio, who says, “Hey, I can postpone this for you.”

Hamlet gives an interesting little speech, again not in iambic pentameter but prose. creating an allusion to something Jesus Christ said to his followers:

Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? and one of them shall not fall on the ground without your Father. . .

Hamlet says “there’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow,” suggesting that God pays attention even to that fall. But here’s the interesting part, which most of Hamlet’s audience would have known–what follows that line:

Fear ye not therefore, ye are of more value than many sparrows. (Matt. 10: 27-29)

Hamlet seems to take new strength and resolve here, likely recalling the rest of that line to “fear ye not.” He realizes that someday, he’s going to die, and the God already knows that time and day. Maybe it’s today, maybe it isn’t. Does that matter? As if knowing his great worth and finding new faith, he says,

“If it be now, ’tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come—the readiness is all. Since no man of aught he leaves knows, what is ’t to leave betimes? Let be.”

Quickly a crowd forms for the duel, and although Hamlet is the first one pricked with the poisoned sword, he’s the last one to die because it’s more dramatic that way.

But first, Hamlet tries to make up with Laertes, apologizing and essentially blaming his insanity for his problems. So if Hamlet really is just faking his insanity, then . . . this explanation is a load of tosh. But if he is crazy–and thinks he may be–then it’s a legitimate apology. So which is it?

Here’s a helpful graphic to keep the next few minutes straight:

In fencing, there’s not supposed to be any blood drawn, so when Laertes and his sharp blade nicks Hamlet, Hamlet’s startled and incensed. But before this, notice how quickly Claudius offers Hamlet the poisoned cup with the fancy pearl reward in it? Just one touch on Laertes and Claudius is already panicking that Hamlet might not get stabbed properly.

So keep track here: Hamlet’s stabbed first with the poisoned sword (the stabbing isn’t severe) so he keeps fighting.

Next, Gertrude decides to drink to her son, grabs the poisoned cup, and downs some poison. Do you think she knows what she’s doing? She says to Claudius, who tries to stop her, “Pardon,” so maybe she does? Maybe not? She seems genuinely surprised a minute later to be falling on the ground, dying. Or maybe she blurts out about the poison to warn Hamlet what did her in.

The swords get switched in the middle of this melee to see what’s wrong with Gertrude, and Hamlet stabs Claudius, FINALLY doing what he’s been trying to do for months now. In the 2009 production, it’s merely a flesh wound on his hand. But in some other productions, Hamlet gives him a pretty good whacking with the blade, which likely causes his death. But for good measure, drink your poison too, Claudius! He quickly dies, but from what, not sure.

Which scenario would be more satisfying: 1) that Claudius dies from the poison he made, or that 2) Hamlet actually avenges his father and kills Claudius with the sword? Oh, also that’s poisoned as well–by Laertes, whose family has also suffered because of Claudius–so 3) there’s three ways Claudius dies. Maybe its a combination of all three that kills him off? That’d be most satisfying, I think: everything comes down to bear on Claudius, all at once.

Next on the death clock is Laertes, whom Hamlet wounds with the poisoned blade. Again, some directors stage this as a major stab, that Laertes dies more quickly because of the stabbing rather than the poison on the blade. If it’s the poison, though, then Laertes has killed himself. But if it’s the stabbing, then Hamlet is culpable. Nobly, Laertes forgives Hamlet and asks forgiveness of him, which Hamlet grants.

Can you see how this would be a very difficult murder case to prove? Who killed whom?

Now that all the major players are gone, we’re left with Hamlet who falls into the arms of Horatio to die (yay, Horatio! Best friends forever!). Horatio wants to join Hamlet in death, but Hamlet argues that someone has to set the record straight as to what happened, so that centuries later someone could turn the story into a play, and centuries after that we could read it as a class. (So freaking cool.)

Some argue that, really, Hamlet should be dead by now, but if he’s only nicked, then he does have that “less than an hour” Laertes promised him so that he can make a few speeches. (Shakespeare made sure of that. Can’t just have the hero drop without last words, and lots of them.) Hamlet suggests that Fortinbras will take over, and that he has Hamlet’s vote, and with that, he’s gone.

The 2009 production ends there, but in the play, the audiences in Shakespeare’s time would have wanted more of a wrap-up. Enter Fortinbras and friends, fresh from the win in Poland, to walk into this blood bath. They have news:

And Fortinbras’ ambassador wants thanks for the deed, but for rudeness–everyone of importance is dead!

Fortunately Fortinbras is a little more level-headed, recognizes sort of what’s going on, and declares that Hamlet should be given all honors as if he’d been king, because he would have been a good one.

And that, my friends, is the story of how Fortinbras beat Denmark without even raising a sword. Yep, after everything, Fortinbras wins.

Wow.

As a foil for Hamlet, he’s perfect. Do you remember what day Hamlet was born? The day his father Hamlet Senior defeated Norway and Fortinbras’s father. What day did Hamlet die? The day Fortinbras Junior takes over Denmark, fully avenging his father’s defeat 30 years ago. It’s as if Fortinbras has been living his own play in the distance, and at the beginning and very end it intersects Hamlet’s play, bringing a conclusion to both of their stories.

Man, that’s so beautiful. Not only is Shakespeare brilliant with language, depth, and breadth, but he creates incredible plots that come together at the end. (So I can easily forgive him for that deus ex machina “helpful pirate” bit earlier.)

HOMEWORK: Now we can’t let this go without one last Hamlet Essay, and this one, you get to choose. HERE are SIX PROMPTS from which you get to CHOOSE ONE to write about. These are all from past AP Exams, and each could use Hamlet to complete them. Choose which one appeals to you the most and write your last Hamlet Essay. Spend only 40 minutes on it. This will be due tomorrow.