Huck Finn, Chapters 1-3

LESSON

Welcome to the world of Huck Finn! Where a teenage boy, uneducated and with no real family of his own, has a small fortune ($6,000 would be equivalent to about $165,000, and the $1 each boy gets per day would be the same as $27 today). And he can’t bear to be cooped up inside. (Can any of you relate? To the cooped up part, not the making bank part.) He can’t bear being “sivilized,” and what that means will become a big part of this novel.

And yes, the misspelling are intentional. It’s part of Twain’s characterization of Huck, and also, I think, his way of saying “Do we really know what this word means?”

First, lets talk about some important literary devices at work here. This is the first real novel we’re reading, since we’ve been doing plays, so we have elements we haven’t discussed yet.

Literary Device–NARRATOR!

Let’s look at Point of View (narrator): our narrator is 13-year-old Huck Finn, and everything we see will be through his eyes. And his views are definitely different. He sees things almost opposite of everyone. For example, he says that the Widow Douglas calls him “a poor lost lamb” but she “never meant no harm by it.” Now, we’d see calling someone a lost lamb as a term of endearment, of worry and concern, but apparently Huck thinks it’s some kind of insult.

Just these first few chapters gives us a big insight into our narrator, and that we’re going to see the south, and the world, through very different eyes!

Here’s something else we need to ask—is this narrator reliable? Meaning, can we trust Huck to show us everything accurately, or are his biases and ideas going to taint just about everything we see?

And more importantly—is that good or bad? (Hint: it’s not necessarily bad.)

Because we have a first person narrator, and everything is going to be from his point of view, we need to sometimes step back from him and consider what he’s seeing and experiencing, and try to interpret it for ourselves. Also understanding that Huck is still young–only about 13–he’s going to understand things differently than adults would.

And that’s exactly what Mark Twain was hoping we’d notice: adults often “justify” attitudes and behaviors (ever heard the story of The Emperor’s New Clothes?). But children quite often see around the justification and excuses, and see only what’s directly in front of them, which, Twain was trying to say, was often more accurate and truthful than what society was trying to hold up.

So we’re going to see a sometimes painfully accurate point of view, first person narrative (pretend I’m writing all of this up on the board) when we read.

Just look at his understanding of the “good place” and the “bad place” and why he’s prefer to be in the “bad place.” Huck is deadly honest–he doesn’t have any craft or guile in him–and he calls it as he sees it.

Why would Twain create a character like this? Because through Huck, Twain gets to say everything he wants to, and all the blame falls on “young, innocent, uneducated Huck.” Never mind that an older, crotchety, well-educated man is actually saying all these things. Our author is hiding behind his narrator, and that gives him immense freedom! Twain was very clever, knowing he could never point a finger at a hypocritical society, but that an innocent boy certainly could.

Now, Huck Finn began as a character in Twain’s earlier book, Tom Sawyer, which has a different tone and purpose. However, we see Tom Sawyer here in these early chapters and, as a mom of five boys, and I can tell you I’d NEVER want a son like Tom!

(Huck–sure. I’d take him. He’s grown on me. But Tom? I’d send him off to a residential treatment center for clinically insane because this boy is MESSED UP!)

Tom wants to create a club! And what a fun club it is! With blood oaths! So they can rob and murder! (All in good fun, mind you. Uh, no. Get this kid LOCKED UP!)

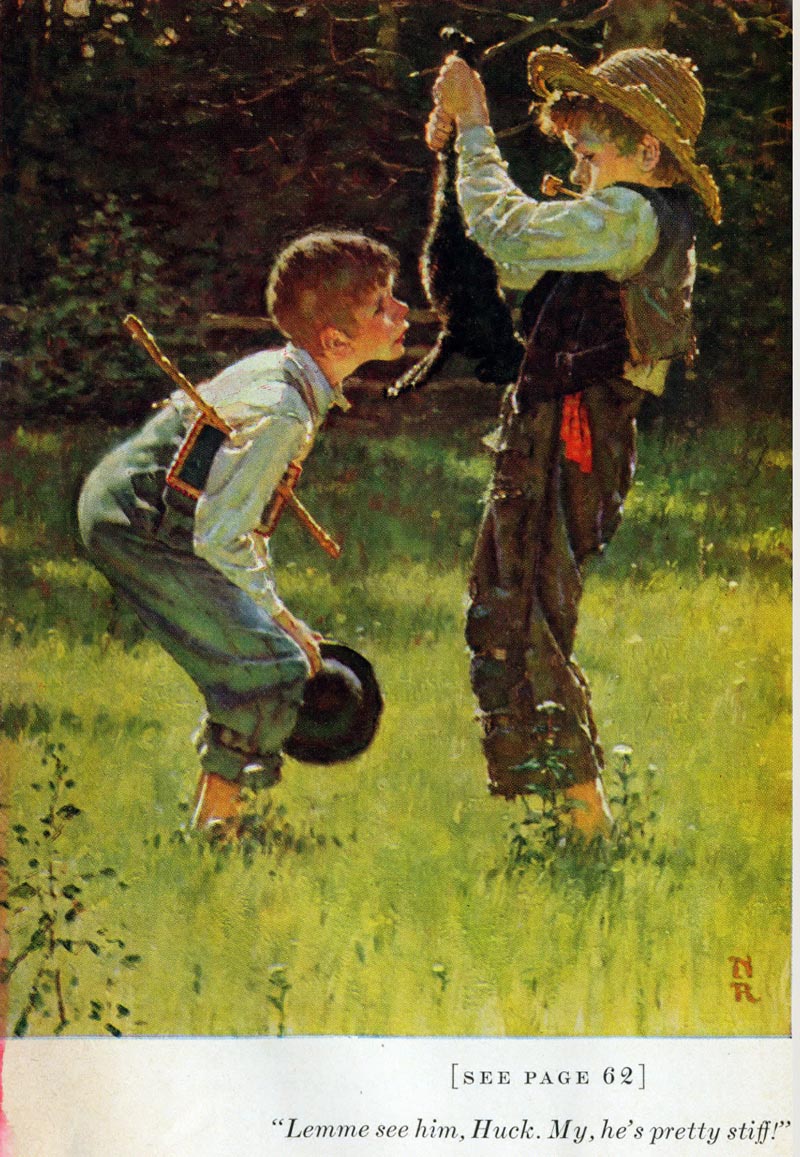

Huck has some real horse sense–for example, he knows his father isn’t the dead body found floating in the river, because it should be face down, not face up which is how a woman would float. Huck, you’ll soon discover, is very clever and can get out of a number of scrapes because he’s aware of his surroundings and knows how to read a situation. (Unlike Tom who thinks it’s a great idea to raid a Sunday School luncheon pretending they’re Arabs with camels and elephants. I mean, WHERE ARE THIS BOY’S PARENTS?! Can’t they tell he is three legs short of a full horse?)

But perhaps it’s telling that Tom says of Huck, “It ain’t no use talking to you, Huck Finn. You don’t seem to know anything, somehow–perfect saphead.” This, coming from the sappiest-head kid ever created in literature. If Tom doesn’t approve of you, then you MUST be good! (Can you tell I really don’t like Tom? He’s that boy your mom warns you about. But Huck doesn’t have a mom–she’s died, and that’s why two old women have taken him in to sivilize him.)

Huck is naturally cynical, as you’ll soon discover. A realistic philosopher, if you will, questioning everything (again, Twain hiding behind his narrator). Huck also is suspicious of “romantic nature.” Tom is all about “romantic nature,” as you can tell by his elaborate oaths and doing things “by the book.” There were many novels in the 1800s which were over-the-top romantic and adventurous, and it often feels in this book that Twain is taking digs at those, trying to show that the romantic view is distorted and causes more problems than its worth.

But while Huck is clever and cynical, he’s also uneducated and very, very superstitious, as is Jim. We see him here after Tom and Huck lead him to believe that he’s been captured by witches, and soon that tale spins wildly out of control for Jim, although it makes him quite popular for a time among the other slaves. We’re going to see much more of Jim later, but what are your first impressions of him? Keep those in mind as we read.

Literary Device–Diction!

So now you’ve seen the very different language style of Twain. He writes in a few diction styles, which takes a great ear to translate.

Why bother doing this? Remember that diction helps establish the TONE--the attitude of the author toward the writing. What kind of tone do we have here? A very relaxed, colloquial tone. You can really hear a kid talking here, rambling even, going all over the place as he tells his story. Some of the sentences are very long, grammar mistakes abound, some spelling is questionable, and all of it translates to creating a laid-back, child-like, almost carefree feel to the novel=the novel’s VOICE (personality, etc. You can’t tell, but I’m pointing to that definition on the whiteboard.).

Twain was the first to do this–no one had attempted to write an entire novel in “slang” like this before, and his boldness inspired thousands of authors after him to experiment with language, voice, and tone.

READING ASSIGNMENT: Read Chapters 4-7

WATCHING ASSIGNMENT: Yes, I know this is new–just slipped this in here. Watch a few minutes of this video which takes you down the Mississippi River. The next few chapters are going to get us to the river, and it helps to have an understanding of just how immense it is:

This map is also helpful for the rest of the book:

WRITING ASSIGNMENT: Continue your Huck-on-a-Log by answering these questions. Write COMPLETE SENTENCES, and give 2-4 sentences for each answer:

- 1. Why did Huck give his money to Judge Thatcher?

- 2. Describe Pap Finn. What kind of a person is he?

- 3. What is Huck’s attitude towards his father?

- 4. Why does Pap yell at Huck for becoming civilized? Is he right?

- 5. What was Huck’s plan of escape from his father?

- 6. How do you know that material things don’t matter to Huck?

AND A POEM!

We’re going to do poetry mixed in here, and Emily Dickinson is a great place to start. Read “Hope is a Thing with Feathers” and spend just 10 minutes annotating it. You do NOT have to write up anything about it–yet. We’ll discuss it tomorrow. But read it, write it (either online some way, or print it and mark it up at home) and watch for tomorrow’s lesson.