Prose Prompt Practice #2–the 2018 Exam Question

Here’s our Zoom Meeting from this morning with Period 1. Period 4 will be similar (but not recorded). Watch this to clarify what’s discussed below:

First, let’s address a few issues I saw in yesterday’s assignment:

- Something horrible happened over the past two weeks: many of you have lapsed back into wordiness. You’re wasting a lot of time to get to the point. Don’t. Sorry, but intros like this are useless because they say nothing: “Twain uses many literary devices to characterize Pap Finn. Some of these devices are imagery, dialect and behavior. These all show what kind of a person Pap is.”

NO! Cut and get RIGHT TO THE POINT: “Pap Finn is an insecure, abusive, disgusting father, which Twain illustrates through gross imagery, poor grammar, and threatening behavior.” That’s all your intro needs to be. State exactly what he is and how we know it. - Do NOT waste time defining lit terms or devices. Trust me–the readers know what they are. “Diction is the choice of words that an author uses . . .” NO! Cut and MAKE YOUR POINT!

- Stick to the passage. If you can’t prove it from the passage, do NOT assume it or pretend it’s there.

- Any assumptions you make you MUST prove them. I will not buy a suggestion that maybe Pap actually loves his son. I see no love in that passage. Prove it!

- TIGHTEN your sentences! They’re fluffy again–STOP IT! We hate fluff! Do you know what fluff means? You’re afraid to get to your point. You’re stalling. It’s weak! Stop being weak!

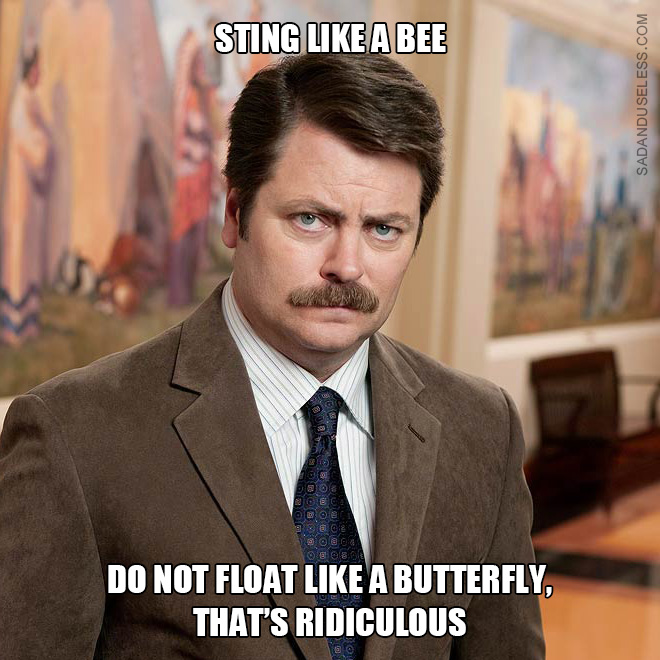

- Ask yourself, “How would Ron Swanson write this?”

Or when you are hesitant when you write, or are making any of the errors above, think of me glaring at you like this. Remember–we HATE fluff:

We’re going to do something a little different today. On Wednesday, someone on the AP Lit Facebook page posted an interesting assignment that I realized would pair well with the prompt writing you just completed. So you’re getting today the same assignment that about 50 other schools (judging by the amount of teachers like me who said, “Ooh, good idea. Going to steal this, thanks!”).

Here’s the assignment: Read the passage as if you were to write the essay. Take notes as you read it. If you can, print it out and annotate it. It’s Question 2 (on page 3). https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/apc/ap18-frq-english-literature.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3SxWPG-btazBNmk-dz_Z1NbOEKLhosR7sNdtTH6HtDJowdpDYtSr0BT20 (This is the exact exam students took two years ago–Rosemary, Mailena, Hailey Bell, Isaac, etc. Yes, pity them.)

Take a close look at the prompt: ” . . . analyze how Hawthorne portrays the narrator’s attitude toward Zenobia through the use of literary techniques.” This is similar to the Huck Finn “analyze the character” prompt and what literary techniques were used. This is wanting you to look at how the narrator feels about the woman he’s addressing. So first discern how he feels about her, then look closer at the text to see WHAT methods Hawthorne used to show us those feelings.

Now, once you’ve read through this, then made some notes for yourself, do NOT write the answer yet. Instead, read the blog below where two of the AP Exam readers/scorers discuss what students did wrong and right in writing this essay:

READ this blog http://www.aplithelp.com/question-2-reflection/?fbclid=IwAR17CIypnKQwaX7QVRX7eXruaidQROoogWdjc0PFKyQr12BotPxoHPbj2X4 Pay particular attention to the “take away” advice.

THEN write me out an OUTLINE of how you would answer this question. You do NOT have to write a full essay (if you want to, you certainly may), but create an outline with examples of what you would write, now that you know what’s the “right” thing to do.

(I learned from this blog that they do NOT like the word “diction” sitting all alone–it’s rather obvious that the author uses words–so avoid it. I also read on another blog that they HATE the phrase, “paints a picture” because every other student uses it. And they’re right; I haven’t finished grading but seven of you have used this phrase. Yeah, way overused.)

Try to avoid the errors the readers/scores explained in their blog. This outline will be due FRIDAY before midnight.

(I will give you another assignment of satire reading on Friday, but that won’t be due until Monday.)