Huck Finn, chapters 8-11

Let’s look at some of the language in here. We could look at any page, but I chose one from chapter 9. This is a great description, and look at the sentence length here as he describes a thunderstorm:

We put all the other things handy at the back of the cavern. Pretty soon it darkened up, and begun to thunder and lighten; so the birds was right about it. Directly it begun to rain, and it rained like all fury, too, and I never see the wind blow so. It was one of these regular summer storms. It would get so dark that it looked all blue-black outside, and lovely; and the rain would thrash along by so thick that the trees off a little ways looked dim and spider-webby; and here would come a blast of wind that would bend the trees down and turn up the pale underside of the leaves; and then a perfect ripper of a gust would follow along and set the branches to tossing their arms as if they was just wild; and next, when it was just about the bluest and blackest—FST! it was as bright as glory, and you’d have a little glimpse of tree-tops a-plunging about away off yonder in the storm, hundreds of yards further than you could see before; dark as sin again in a second, and now you’d hear the thunder let go with an awful crash, and then go rumbling, grumbling, tumbling, down the sky towards the under side of the world, like rolling empty barrels down stairs—where it’s long stairs and they bounce a good deal, you know.

Why such long sentences? Probably to keep the feel of the storm as one great emotion?

I love the description of the thunder, like empty barrels rolling down stairs . . . and they keep going. This sounds and feels like a young teenager, and immediately everyone knows exactly what he’s feeling. The voice here really works.

What’s your mood when you read these lines? Is it frightening? (I don’t think so.) It would get so dark that it looked all blue-black outside, and lovely;

The language is almost poetic: thunder let go with an awful crash, and then go rumbling, grumbling, tumbling,

A student last year (Matias) notice that there’s a lot of subtle spider images in this book. Here’s one of them: the trees off a little ways looked dim and spider-webby.

Look at this fun personification: then a perfect ripper of a gust would follow along and set the branches to tossing their arms as if they was just wild;

Hearing these words come from an adult protagonist would be odd. But from a kid? It just works so well!

Here’s another collection of great lines from Huck and Jim:

- “There’s something in it when the widow or the parson prays, but it don’t work for me.” (This makes me so sad for him! Still, he got his bread, right?)

- “saw a man . . . It most gave me the fantods.” (I have NO idea what fantods are, but we really should be using that word more.)

- Jim said bees wouldn’t sting idiots; but I didn’t believe that, because I had tried them lots of times myself, and they wouldn’t sting me. (He doesn’t even realize he’s not an idiot.)

- “Doan’ hurt me—don’t! I hain’t ever done no harm to a ghos’. I alwuz liked dead people, en done all I could for ’em. You go en git in de river agin, whah you b’longs, en doan’ do nuffn to Ole Jim, ’at ’uz awluz yo’ fren’.” (I just love poor Jim–“Hey, I always liked dead people, so just go away or something, please.”)

- They’re looking for signs, especially bad one. Why would you care about good ones? “Ef you’s got hairy arms en a hairy breas’, it’s a sign dat you’s agwyne to be rich.” (No, it’s not. I’m still not rich.)

- Yes; en I’s rich now, come to look at it. I owns mysef, en I’s wuth eight hund’d dollars. I wisht I had de money, I wouldn’ want no mo’.” (Wow–think about that: he owns himself, and he owns a lot then.)

Then there are some sections that just crack me up, like this:

[When they’ve found the wooden leg.] The straps was broke off of it, but, barring that, it was a good enough leg, though it was too long for me and not long enough for Jim, and we couldn’t find the other one, though we hunted all around.

WHY WOULD SOMEONE HAVE TWO WOODEN LEGS?!

But they also get some good supplies from that house, so that’s all right. Mighty convenient, an entire house coming down the river. But if you looked at the video I posted yesterday, and consider that houses in the 1800s weren’t secured to their foundations very well, it’s easy to see how a whole house on the banks when it’s flooding would go downstream.

Bad luck: Notice how they’re always waiting for it? It may be delayed for days or even years, but it’s coming! Superstitious people who don’t understand cause and effect (because they aren’t very well educated) put a lot of “faith” in luck, mostly bad. Because they can’t read circumstances, or have limited knowledge as to how events unfold, they can’t predict what bad thing may happen. To them, it’s all mysterious–or bad luck.

I’d always felt that looking at a new moon over your left shoulder was one of the most careless and foolish things a person could do. Old Hank Bunker did it once and bragged about it. In less than two years, he got so drunk that he fell off the shot-tower.

But seriously, sticking a rattle snake in someone’s bed? That’s just stupid, Huck! And eventually he figures that out.

Huck also learns how to be a girl, kind of. Try this at home: Have someone toss you something that you catch with your lap. Or try threading a needle. Hmm, I don’t think these “tests” are applicable anymore.

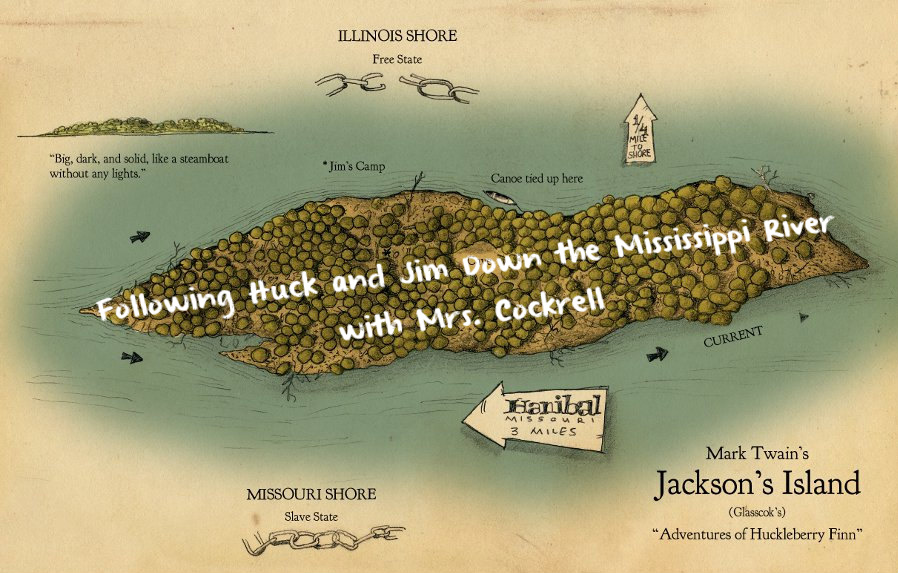

At the end of this reading, Huck and Jim are leaving the island ahead of people looking for Jim. Now begins their grand adventure on the river–together.

Here’s some great insights (I think from Spark Notes?)

From this point in the novel forward, their fates are linked. Jim has had no more say in his own fate as an adult than Huck has had as a child. Both in peril, Huck and Jim have had to break with society. Freed from the hypocrisy and injustice of society, they find themselves in what seems a paradise, smoking a pipe, watching the river, and feasting on catfish and wild berries.

Huck and Jim are reminded that no location is safe for them.

These two incidents also flesh out some important aspects of the relationship between Huck and Jim. In the episode with the rattlesnake, Huck acts like a child, and Jim gets hurt. In both incidents, Jim uses his knowledge to benefit both of them but also seeks to protect Huck: he refuses to let Huck see the body in the floating house. Jim is an intelligent and caring adult who has escaped out of love for his family—and he displays this same caring aspect toward Huck here. While Huck’s motives are equally sound, he is still a child and frequently behaves like one. In a sense, Jim and Huck together make up a sort of alternative family in an alternative place, apart from the society that has only harmed them up to this point.

Mrs. Loftus and her husband are only too happy to profit from capturing Jim, and her husband plans to bring a gun to hunt Jim like an animal. Mrs. Loftus makes a clear distinction between Huck, who tells her he has run away from a mean farmer, and Jim, who has done essentially the same thing by running away from an owner who is considering selling him.

Whereas Mrs. Loftus and the rest of white society differentiate between an abused runaway slave and an abused runaway boy, Huck does not. Huck and Jim’s raft becomes a sort of haven of brotherhood and equality, as both find refuge and peace from a society that has treated them poorly.

Some money numbers are tossed around–here’s what they mean today:

- Jim’s worth $800=22,800

- Pap reward $200=5,700

- Jim’s reward $300=8,600

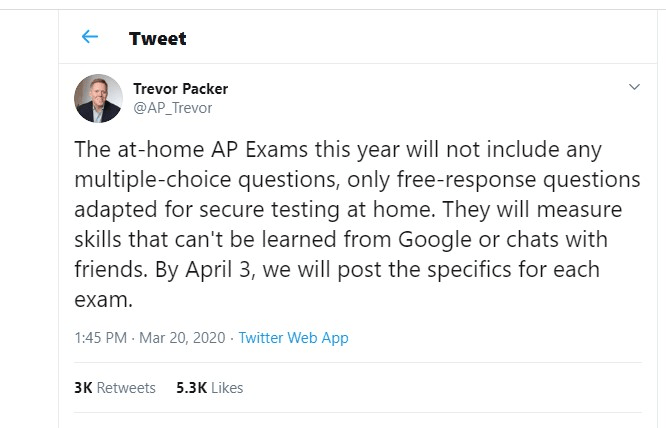

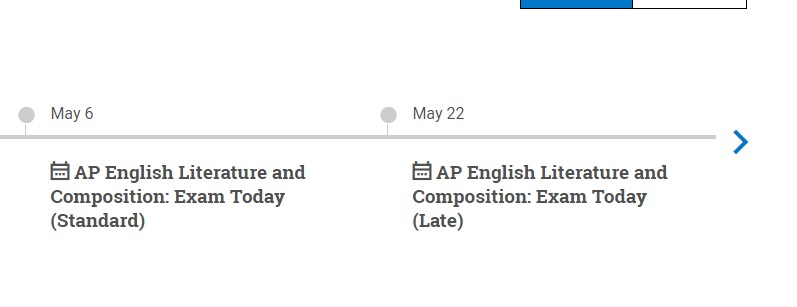

READING ASSIGNMENT: Chaps. 12-14

WRITING ASSIGNMENT:

- 1. Why do Huck and Jim begin their journey down the Mississippi?

- 2. Why do Huck and Jim board the Walter Scott?

- 3. Why does Huck want to save Jim Turner?

- 4. How does Huck send help to the Walter Scott?

- 5. What do we learn about Jim from his talking about “King Sollermun”?

(I’ll assign another poem tomorrow. Just read today and do the questions above.)